Rust continues to grow substantially in the land of programming languages. With a growing community and ecosystem in all areas of software development, including AI, there’s no corner where you can’t apply it. And Single Page Applications are no different.

In this post, we will examine Sycamore, a fantastic reactive UI library (like React) for shipping webassembly to production in Rust.

Sycamore

I accidentally stumbled upon Sycamore while searching for UI frameworks for Rust. I already knew about Leptos and Dioxus, leading names in this front in Rust. Needless to mention Tauri, another titan that sends shockwaves of versatility across the language and community.

What caught my attention was the simplicity in the reactive constructs, the nice macros for properties and state management. We will see some of them in this post.

If you want a deeper comparison between Sycamore, Leptos, and Dioxus, there’s this great article by Vendant Pandey. This article concentrates on “giving it a try” and how it feels in general.

Disclaimer: It’s important to take into account the fact that I’m not a front-end engineer, despite having coded in React in the past and getting somewhat involved in FE hiring and FE projects.

Documentation

Sycamore’s documentation is pretty neat. In Your First App section, you get a good taste of what’s coming, but if you want a complete example, go straight to the Hello World of reactive frameworks: the Todo app example.

I wish the JS Interop page, SSR Streaming page, and the Deploy were more dense. But in general, the doc is good enough for our purposes.

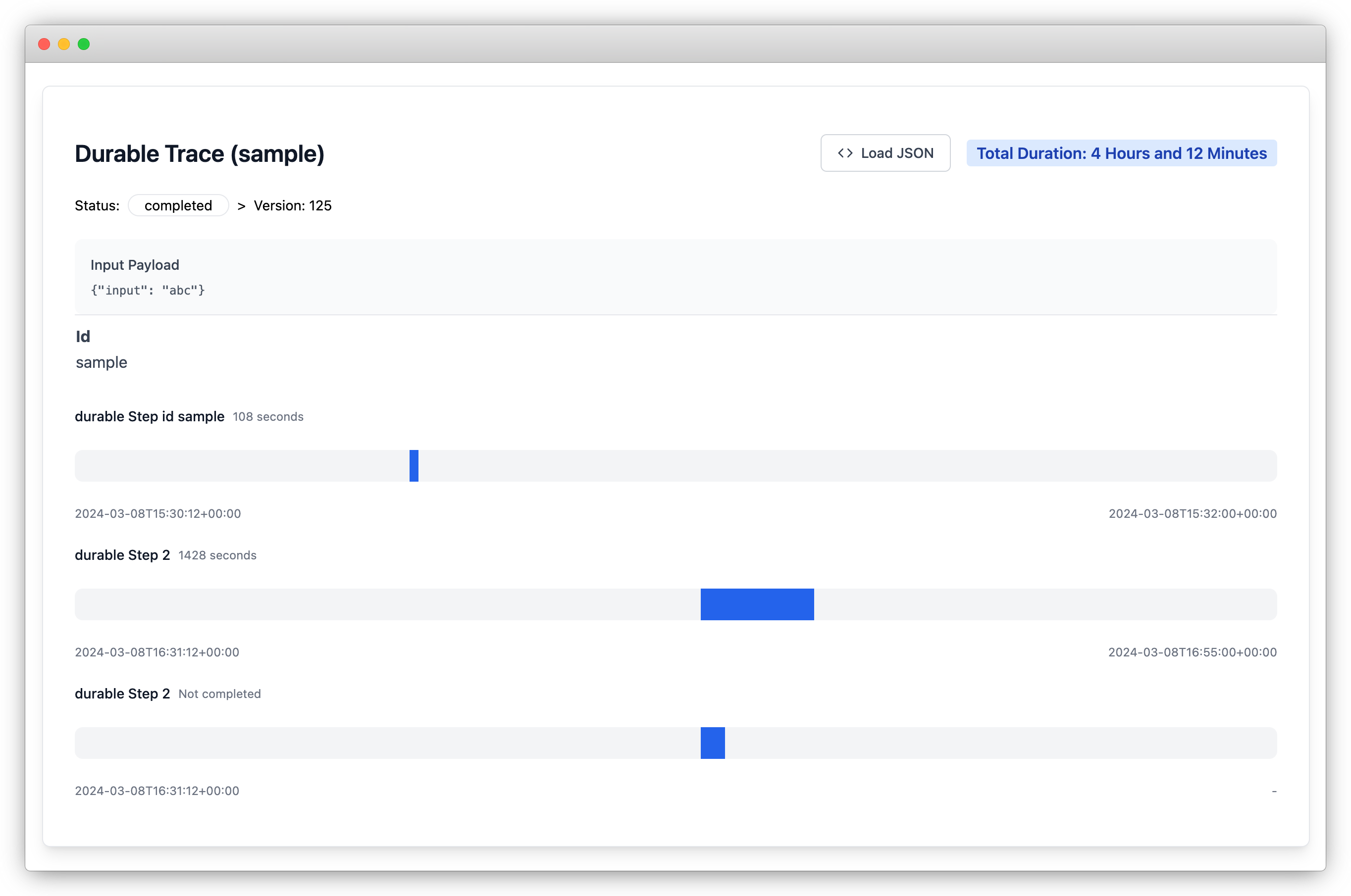

Our SPA

To add some context, recently, I had the chance to build a simplified Durable Execution framework similar to Inngest. The framework will execute almost plain Java code to completion even in the event of failures, redeployments, intentional delays, etc. The framework produces an execution trace (a JSON) that contains valuable information for introspecting the several instances of durable execution running.

Data format

The format is more or less like this:

name- The execution name. It can be something likeApproveExpenses.durable_execution_id- A unique identifier for the execution.scheduled_at- The scheduled time for the durable execution.completed_at- The actual completion time of the durable execution.steps- An array of individual steps involved in the durable execution

Here’s an example of what each step might look like:

durable_step_id- The unique identifier of each stepresult- The arbitrary JSON that results from a given step when completed. (e.g.{ "ok": false }).inTaskInfo—Some runtime-specific task information. This is very context-specific; just imagine some JSON with lower-level information.outTaskInfo- Some runtime-specific task information.

“Design”

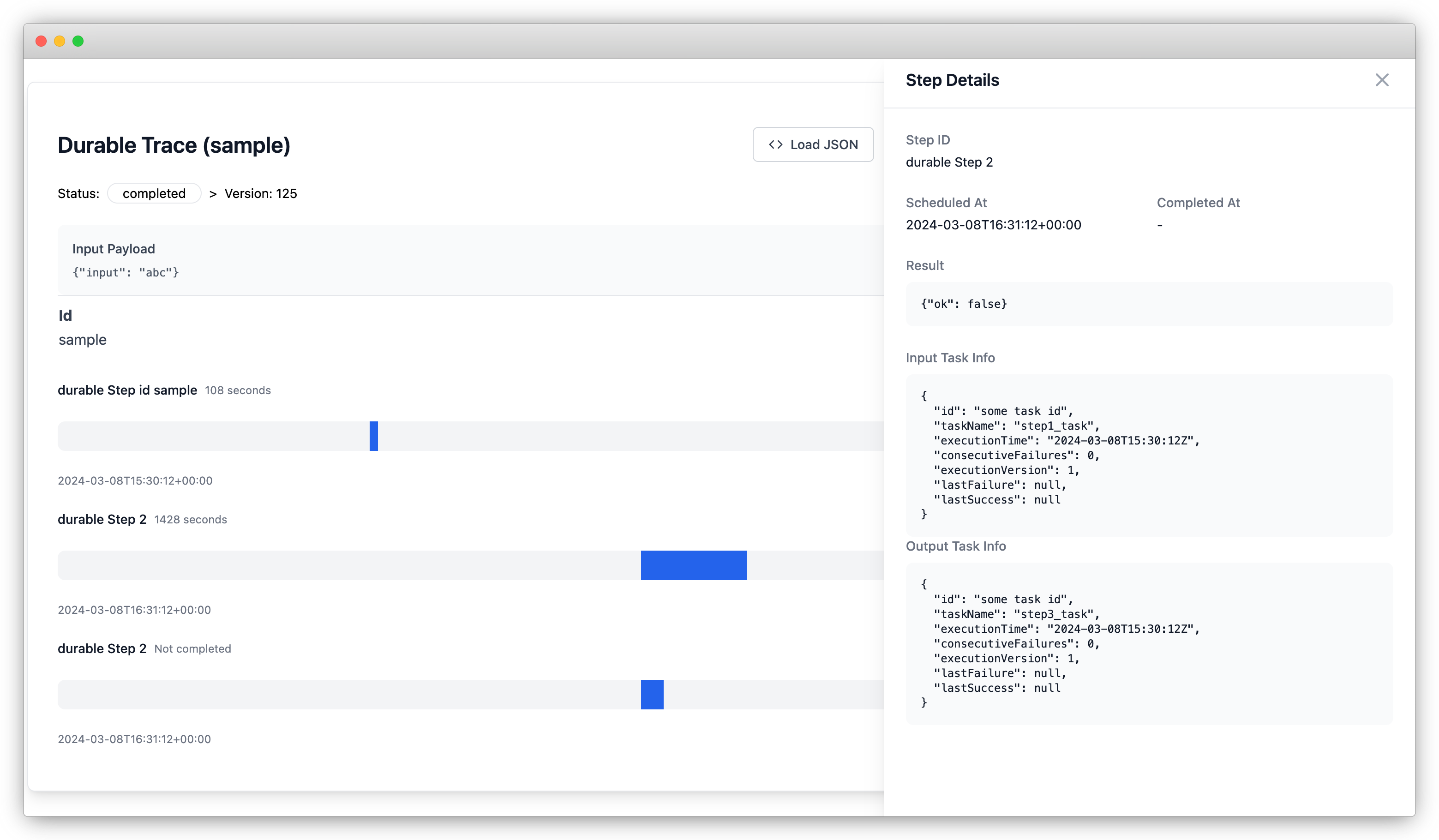

Our page will then require the user to paste the JSON and display the trace. Upon clicking on each step, a side panel will appear showing the specific step detail. Each step will be displayed so that the user can visualize the start, completion time, and duration.

Below we see the sidepanel:

Components

The project was set up with tailwindcss. For that, I just had to use Trunk’s native support for Tailwind. Trunk is a bundler (maybe not the best description) for shipping your Rust code as a web assembly application.

The support for tailwind is described here and requires a single line of code in our index.html:

1

2

3

4

5

6

<!-- ... -->

<head>

<link data-trunk rel="tailwind-css" href="input.css"/>

<link data-trunk rel="rust" data-wasm-opt="s"/>

</head>

<!-- ... -->

The whole code of the SPA is available on GitHub paulosuzart/hello-sycamore, and I would like to explore the approaches I used for handling signals (create_sigal, memos (create_memo) and also rending list (Keyed). All css were striped from the snippets in this post.

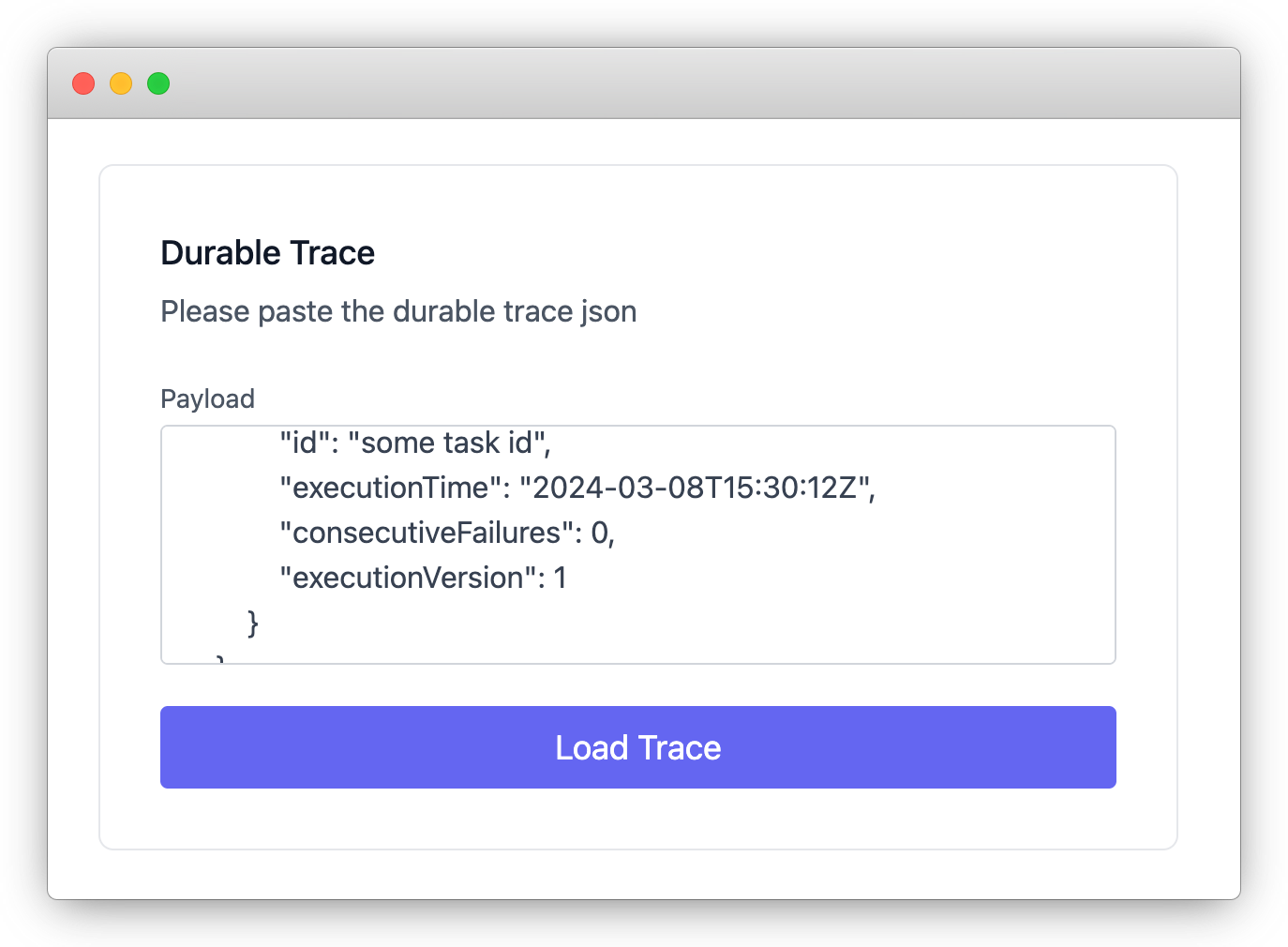

Input

The only way to get data into our SPA is by letting the user paste the trace they can obtain from the running durable framework. We must:

- Show the input text area

- Parse the Json

- Display error, if any. Also, closing the error panel

- Update the application state with the parsed data

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#[component]

pub fn TraceInput() -> View {

let show_error = create_signal(false);

let set_show_error = move || show_error.set(true);

let set_hide_error = move || show_error.set(false);

let err_msg = create_signal(String::new());

let err_msg_read = create_memo(move || err_msg.get_clone());

view! {

(if show_error.get() {

view! {TraceInputErrorModal(on_hider_error=set_hide_error,error_msg=err_msg_read)}

} else {

view! {TraceInputText(on_error=set_show_error, err_message=err_msg)}

})

}

}

The TraceInput component is responsible for the four aspects above. To display an error, it uses a signal, which is passed to TraceInputErrorModal. Notice how TraceInputErrorModal also takes a on_hider_error property. This function will be used on the close icon of the error modal. The view! macro will swap between showing the error message or the text input by simply setting it to false.

This same signal (show_error) is also used by TraceInputText to set the value to true.

I want to highlight the pattern I used: signal + toggle on (set_show_error) + toggle off (set_hide_error). What I liked about this pattern is that the action of toggling the error modal is transparent to the components involved. Let’s see how it feels in the input component:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

#[component(inline_props)]

fn TraceInputText<F>(on_error: F, err_message: Signal<String>) -> View

where

F: Fn() + Copy + 'static,

{

let state = use_context::<State>();

let payload = create_signal(String::new());

let parse_json =

move |_| match serde_json::from_str::<DurableTrace>(payload.get_clone().as_str()) {

Ok(p) => {

state.0.set(Some(p));

}

Err(e) => {

console_error!("{}", e);

on_error();

err_message.set(e.to_string());

}

};

view! {

div {

h2 { "Durable Trace" }

p { "Please paste the durable trace json" }

div {

label { "Payload" }

textarea(bind:value=payload, id="payload", name="payload")

}

button(on:click=parse_json ) { "Load Trace" }

}

}

}

Check the bound value to the textarea. It’s a signal for a payload. When filled, the underlying value will match the value of the input. Then the button on:click calls our parse_json. Here is where we may call on_error() (that setter for our signal passed as property for the input component). It is transparent.

If all is good, the app global state captured by use_context::<State>() is set. The State is defined as the following:

1

2

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)]

struct State(Signal<Option<DurableTrace>>);

Finally, let’s check the TraceInputErrorModal:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

#[component(inline_props)]

fn TraceInputErrorModal<F>(on_hider_error: F, error_msg: ReadSignal<String>) -> View

where

F: Fn() + Copy + 'static,

{

view! {

div {

div {

div {

button(on:click=move |_| on_hider_error()) {

svg {

path(fill-rule="evenodd", d="M4.293", clip-rule="evenodd")

}

}

}

div {

svg {

path(stroke-linecap="round", stroke-linejoin="round")

}

h3 {

"Invalid Json. Please paste a valid durable trace json:"

}

p { (error_msg) }

}

}

}

}

}

Here, we react to the button click by calling it on_hider_error. It is very transparent. There is also a ReadSignal created by let err_msg_read = create_memo(move || err_msg.get_clone());.

Step List and Details

Steps are the powerhouse of this framework. They execute the computations. In addition to the main visualization in a list, there’s the detail side panel.

The list Uses the Sycamore’s Keyed function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

enum StepDetailEnum {

NotSet,

Loaded(StepTrace),

}

#[component(inline_props)]

pub fn Steps(

steps: Vec<StepTrace>,

durable_scheduled_at: DateTime<Utc>,

durable_completed_at: Option<DateTime<Utc>>,

) -> View {

// ...

let step_detail = create_signal(StepDetailEnum::NotSet);

let on_hide_step = move || step_detail.set(StepDetailEnum::NotSet);

let on_show_step = move |step| step_detail.set(StepDetailEnum::Loaded(step));

view! {

div(class="space-y-6") {

Keyed(list=steps,

view=move |step| view! {

StepItem(max_completion=max_completion,

delta_window=delta_window,

second_rate=second_rate, step=step,

on_show_step=on_show_step)

},

key=|step| step.durable_step_id.clone())

}

(match step_detail.get_clone() {

StepDetailEnum::Loaded(step_trace) =>

view! { StepDetail(step_trace=step_trace, on_hide_step=on_hide_step) },

StepDetailEnum::NotSet =>

view! {},

})

}

}

There are other ways of rendering a list, but I found this method particularly useful and concise, even though I don’t need to update this list.

Now, check the usage of let step_detail = create_signal(StepDetailEnum::NotSet);. Instead of a bool + Option to control the rendering of a signal, this component uses a enum to keep track of several variantes of a signal internal state. For the example we use use Loaded(StepTrace) and NotSet, but we could use Loading, among other variants to handle spinners, etc. This pattern offer a more fine grained control of rendering.

The created signal used by the next two modifying state closures. They are then passed to StepItem and StepDetail respectively, to show and hide the side panel of a step. This pattern keeps a good encapusation of behaviour by keeping interactions with the signal close to it.

State and Local Store

We saw use_context straight from a component to interact with the application state without passing it several nested levels of components. The state is provided at the upper level of the application (before the main components are rendered).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

fn main() {

sycamore::render(|| {

let state = State(create_signal(None));

provide_context(state);

App()

})

}

The state starts totally empty, though. And to persist the data in the user’s browser, some tricky is needed to keep the json in localStorage.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

#[component]

fn App() -> View {

let state = use_context::<State>();

let local_store = window().local_storage().unwrap().expect("No local storage");

let saved_trace: Option<DurableTrace> = if let Ok(Some(trace)) = local_store.get_item("trace") {

match serde_json::from_str::<DurableTrace>(&trace) {

Ok(trace) => Some(trace),

_ => None,

}

} else {

Default::default()

};

state.0.set(saved_trace);

create_effect(move || {

state.0.with(|trace| {

if let Some(trace) = trace {

local_store

.set_item("trace", &serde_json::to_string(trace).unwrap())

.unwrap();

}

})

});

//...

}

The function create_effect is used to “follow” all the mentioned effects and create side effects (persist to the local store). The call to state.0.with will do the trick , and on each change (when the user successfully parses a JSON), the local store is updated. The App component is also responsible for reading the localStore and restoring the application state from it.

Conclusion

A note: here is a quick note before we wrap up. Zed and RustRover struggled quite a bit to handle the project, whilst VSCode always worked out of the box. I was surprised to see RusRover needing help dealing with the macros, autocompletes, etc.

It was a pleasant experience to play with Sycamore. It is complete enough to create pretty complex applications. However, it is clearly behind the competition in terms of documentation and ecosystem. I don’t know how they plan to chase Dioxus and Leptos. One area that requires some attention is testing, which is currently a work in progress.

Another point that is not positive is the macro used for HTML elements. It uses a notation like div {} as opposed to Leptos that uses <div></div> notation more natural to html and speeding up some work.

Webassembly is also growing beyond the web browser. Fermyon is a great example of serverless backed by web assembly applications. Webassembly portability is in its early days of exploration; I’m sure more will come soon.

Feel free to access the app at https://hello-sycamore.vercel.app/. You can use this JSON as an example here. This project also contains a GitHub actions workflow for deploying the compiled project to Vercel as satic content.

I hope you enjoyed the content!