OCaml first appeared back in 1996, and to this day, it’s a loved language with great tooling, libraries and content. Even The Prime Time surrendered to the beauty of the language.

This post will discuss my end-to-end experience with OCaml, from implementation to testing to publishing a package and using it “in production” while building starred_ml, an OCaml awesome-README generator for your starred GitHub items.

The links above are just a few examples of what you can find in OCaml’s ecosystem. You can find much more in the OCaml Plante and Weekly News, for example.

If you are unfamiliar with the language, the best starting point is always the language website.

Disclaimer: this post is not meant to be a tutorial on the tooling details or the language but a journey. I’ve been more deeply involved with the language for one year after previous on/off interactions. Thus, I left links to relevant content along the way.

Ecosystem at a Glance

As you may have noticed, I love programming languages. Not how to implement and create one, but more on the usage side: which features they have and how they can make us productive in building, testing, and maintaining our systems. I am passionate about exploring languages and having the Go-To tool for the problem.

Another critical aspect of the language is the surrounding ecosystem. Without tooling, the most beautiful language will give engineers a hard time if there’s no support in terms of package managers, build tools, monitoring, testing frameworks, etc.

OCaml has a great ecosystem that can help you get started today:

- opam - OCaml Package Manager. It’s the mix of nvm and npm for Node. With

opam, you are able to install several versions of OCaml and then install dependencies. It also offers the concept of a switches that works like python virtual envs. - Dune - The de facto build tool for OCaml projects. It acts as the

npmfor Node. It manages your dependencies and triggers tasks liketest,build,exec,etc. - dune-release - If wanna publish your package to opam packages.

You can quickly get up and running with opam and dune. Here are some tips extra tips:

- ocaml-platform - You can use this VSCode extension that works amazingly well.

dune fmt- It formats your code, and I love this. Don’t let your engineers waste time debating whether aletand=should be on the same line. Just go for the standard formatting.dune test- You can use alcotest anddune testwill execute your tests.dune exec {package_name}- to run the project you are building.

starred_ml for awesome-like README

We now know some directions for the language and ecosystem, and the best way to solidify knowledge is by building something more or less useful. Generate a README with my starred items on GitHub, which could be an opportunity. The final result is here at paulosuzart/awesome.

The flow is quite simple:

- fetch all links at github.

- sort and group them so they can be displayed per language.

- dump the content in a

README.md.

For this we will need:

- an HTTP Client that can talk TLS: here we use cohttp by mirageOS

- a JSON parser: there’s a fantastic lib called yojson. We are covered.

- a way to get arguments from the command line or env var: OCaml is blessed with cmdliner, one of the best cli frameworks I have tried.

- a template engine like jinja2 to give shape to our README: jingoo is essentially the jinja2 of OCaml.

- a conversion from language names to url encoded values, so links don’t get broken within our README: also check! There’s a Jingoo built-in filter

url_encode. - a testing library: again from mirageOS, alcotest is a popular framework that can help us here.

A bit of code here and there

The whole code is relatively small, but walking through it entirely here is not worth it. I want to save you some energy by getting to the end of the article and seeing how I had to deal with publishing a package to opam. You might be able to help me with a limitation there.

GitHub API Model

OCaml can have “header” files to define the interface of a module. By the way, modules in OCaml are not as intuitive as in other languages. It is just another way of seeing things that are a bit confusing.

Back to the point, I created a Github module with the types to hold the API responses, as well as some other basic operations on the data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

(** lib/github.mli *)

type owner = { login : string }

[@@deriving show, yojson { strict = false; exn = true }]

type starred = {

name : string;

description : string option;

topics : string list;

language : string option;

html_url : string;

owner : owner;

}

[@@deriving show, yojson { strict = false; exn = true }]

type starred_response = starred list

[@@deriving yojson { strict = false; exn = true }]

val from_string : string -> starred_response

(** Converts a result page of starred paged result into a list of starred *)

val by_language : starred list -> (string * starred list) list

(** Converts a list of starred items into a struc grouped by language like

[("java", [starred; starred]), ("scala", [starred;...])] *)

val languages : ?default_language:string -> starred list -> string list

(** Return the languages for the repositories. *)

I want 2 things: 1) a type (imagine a struct) to store the response, 2) a way to group them by language. The group by operation could be placed outside Github module, but this way is also fine so we keep operations on starred type provided by the same module.

The module definition above define 3 types:

starred_response, a list ofstarred.starred, each row representing a starred repository.owner, the owner data is placed in a separate sub-structure.

When we use .mli files, we are willing to hide the details of our module’s implementation. The call site doesn’t know how the data is populated. Here is our implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

(** lib/github.ml *)

(** ... *)

let from_string s = Yojson.Safe.from_string s |> starred_response_of_yojson_exn

let language_not_set = "Not Set"

(** group_by_first will group starred items by its language, if present. returns

a assoc list of starred items. The list is sorted by language

alphabetically. Each left value of a language (the list of starred) is also

sorted alphabetically. *)

let group_by_first lst =

let ht = Hashtbl.create 30 in

List.iter

(fun (key, value) ->

let values = try Hashtbl.find ht key with Not_found -> [] in

Hashtbl.replace ht key (value :: values))

lst;

Hashtbl.fold

(fun lang repos acc ->

(* Sorts the language list while folding into the final assoc list*)

(lang, List.sort (fun e e2 -> compare e.name e2.name) repos) :: acc)

ht []

|> List.sort (fun (c1, _) (c2, _) -> Stdlib.compare c1 c2)

let by_language s =

let bz =

List.map

(fun i ->

match i.language with Some l -> (l, i) | None -> (language_not_set, i))

s

in

group_by_first bz

module StringSet = Set.Make (String)

let languages ?(default_language = language_not_set) starred_items =

StringSet.elements @@ StringSet.of_list

@@ List.map

(fun item ->

match item.language with Some l -> l | None -> default_language)

starred_items

Notice from_string uses starred_response_of_yojson_exn to parse from string into our type. This function is generated (via metaprogramming ppx) and is the one doing the internal plumbing of the parse. The suffix exn means it will throw an exception if anything goes wrong. You can see this option set at the preprocessor options on the type:

1

[@@deriving show, yojson { strict = false; exn = true }]

Finally, by_language uses a hashmap to group the starred by the language.

Calling GitHub

We can see where Github.from_string is used after we call GitHub API.

Check down there the result call to Http_util.fetch. It returns a potential result r and a potential next page’ss url. The resulting string r is passed to Github.from_string, and the list of repositories is append @ to acc before the process repeats.

The function is considered the primary function for our project. It’s the point where we run our Eio_main. Eio is the new OCaml Effect-based concurrent environment. I hope I can explore it more, but imagine something like Rust’s tokio for OCaml, offering fibers, promises, etc. A switch is created to be used by the underlying HTTP client.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

(** bin/main.ml *)

let fetch (max_pages : int option) url token template =

Eio_main.run @@ fun env ->

Mirage_crypto_rng_eio.run (module Mirage_crypto_rng.Fortuna) env @@ fun () ->

let client =

Client.make ~https:(Some (https ~authenticator:null_auth)) env#net

in

Eio.Switch.run @@ fun sw ->

let rec fetch_github api_url acc curr_page =

match Http_Util.fetch ~sw api_url client token with

| Some (r, Some next_url)

when Option.value ~default:max_int max_pages >= curr_page ->

fetch_github next_url (acc @ Github.from_string r) (curr_page + 1)

| Some (r, _) -> acc @ Github.from_string r

| None -> acc

in

let content = fetch_github (Format.sprintf "%s?per_page=100" url) [] 1 in

Eio.Stdenv.stdout env

|> Eio.Flow.copy_string @@ Util.print_content content template

After fetching all the pages, the content is now passed to Util.print_content. At this point, the starred type gets converted to Jingoo’s structure. Let’s check it out:

Jingoo

Before rendering our repositories, we need to convert everything into types provided by Jingoo. For example, a string must be turned into a Jg_types.Tstr, and an arbitrary type must be turned into a Jg_types.Tobj, that works like a list of tuples associating keys to Jg_types. Here our conversion:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

(** lib/util.ml *)

let print_content items template =

let bz = Github.by_language items in

let unique_languages = unique_lang bz in

let by_language =

List.map

(fun (language, items') ->

Jg_types.Tobj

[

("language", Jg_types.Tstr language);

( "starred",

Jg_types.Tlist

(List.map

(fun i ->

Jg_types.Tobj

[

("name", Jg_types.Tstr i.name);

("html_url", Jg_types.Tstr i.html_url);

( "description",

match i.description with

| Some d -> Jg_types.Tstr d

| None -> Jg_types.Tnull );

("owner_login", Jg_types.Tstr i.owner.login);

])

items') );

])

bz

in

let count = List.length bz in

render_template

[

("lang_count", Jg_types.Tint count);

("languages", unique_languages);

("by_language", Jg_types.Tlist by_language);

]

template

At the end I wanna give to the template just 3 variables: 1) the count of languages, 2) the languages, and 3) the repositories grouped by language.

Tests with alcotest

I wanted to add some tests to have the feel of a complete project with proper build, dependencies, modularization and of course, tests.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

let starred_pp ppf i =

List.iter

(fun (t, p) ->

List.iter (fun z -> Fmt.pf ppf "%s -> %s" t (show_starred z)) p)

i

let starred_testable = Alcotest.testable starred_pp ( = )

let test_group () =

let sample_java_repo =

{

name = "Xample";

description = Some "Description";

topics = [ "Flow" ];

language = Some "Java";

html_url = "example.com";

owner = { login = "auser" };

}

and sample_java_repo2 =

{

name = "Sample";

description = Some "Description";

topics = [ "Flow" ];

language = Some "Java";

html_url = "example.com";

owner = { login = "viola" };

}

and sample_ocaml_repo =

{

name = "Another Repo";

description = Some "Description";

topics = [ "Flow" ];

language = Some "Ocaml";

html_url = "example.com";

owner = { login = "bar" };

}

in

Alcotest.(check starred_testable)

"Repos are grouped by topic"

[

("Java", [ sample_java_repo2; sample_java_repo ]);

("Ocaml", [ sample_ocaml_repo ]);

]

(by_language [ sample_java_repo; sample_ocaml_repo; sample_java_repo2 ])

let option_pp ppf o =

match o with Some l -> Fmt.pf ppf "%s" l | None -> Fmt.pf ppf "No next link"

let testable_link = Alcotest.testable option_pp ( = )

let test_no_next_page () =

Alcotest.(check testable_link)

"A last page returns None" None

(next_link

@@ Http.Header.of_list [ ("Link", "<http://prev>; rel=\"prev\"") ])

let test_next_page () =

Alcotest.(check testable_link)

"A last page returns None" (Some "http://s")

(next_link @@ Http.Header.of_list [ ("Link", "<http://s>; rel=\"next\"") ])

let () =

run "Starred_ml"

[

("Github", [ test_case "Group" `Quick test_group ]);

( "Http_util",

[

test_case "No Pagination" `Quick test_no_next_page;

test_case "Next Pat" `Quick test_next_page;

] );

]

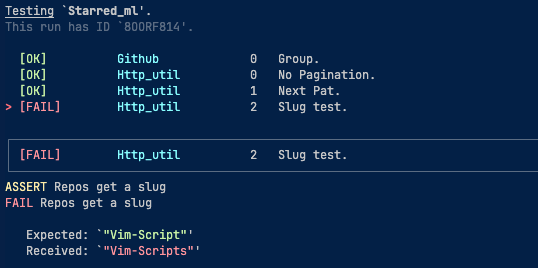

The test output is quite beautiful (I forced one error just to take a screenshot):

Alcotest kind of requires some effort to understand its concepts. For example, they have this idea of a testable; a type that implements a way to pretty-print and test for equality. If you come from more sophisticated assertion libraries like AssertJ, you will need to read a bit of alcotest’s posts on the internet. You can find great content here and here.

The CLI

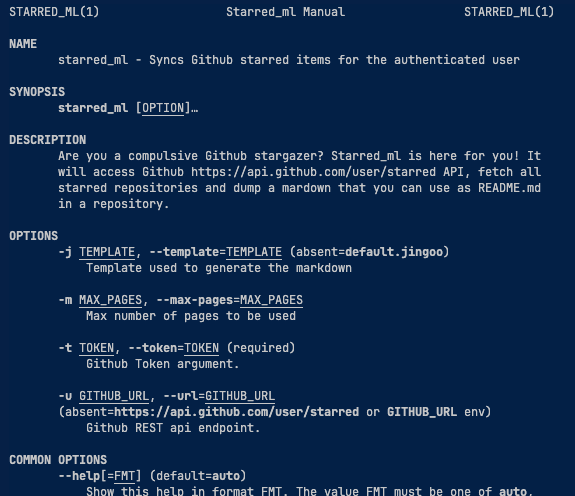

As I mentioned cmdline is impressive. It outputs this manpage-like help that feels very professional and complete:

All options can be set via args or env variables out of the box, as well as defaults, optional, etc. Take a look at the full command definition here. And just to mention one of the command options lets see the max-pages one:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

let max_pages =

let doc = "Max number of pages to be used" in

Arg.(

value

& opt (some int) None

& info [ "m"; "max-pages" ] ~docv:"MAX_PAGES" ~doc)

We are saying it will be a value, which is optional (opt) and is converted to an integer via int or just None if absent.

After everything is parsed and ready, the fetch function we saw earlier is invoked.

Packaging and publishing

The folks at Tarides are doing a fantastic job keeping the OCaml community together and alive. One of their great contributions is dune-release, which helps you publish your package to the opam repository. The best way to see it in use is by checking my GitHub Actions here.

The process consists of calling dune-release tag -y -v. This step creates a tag in our repository. It’s important to have the CHANGES.md in place with the target version like you can see here.

The next step is to generate the distribution archive with dune-release distrib and dune-release publish.

The publish step is where thing turn blurry. It seems that it’s expected to provide a local clone of the opam-repository with enough permissions to push to it. This means you can’t push to the actual opam repository but to a fork. Then, I struggled to make the script create the draft pull request on my own opam repository fork even though I provided --token=$ . I tried all kinds of permissions, but they never worked.

And this is where my automated process ends. After this point I go to my own opam fork and create a PR from my fork to the actual opam repository as you can see here.

The release manager dune-release offers a dune-release bistro, but it hits the same wall. I had to navigate the internal code of dune-release to understand what it was trying to do. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to get to this point. I wil give another fresh try to see if newer releases are doing a better job.

Using

I’m the first user of my own program. Check out my auto-generated paulosuzart/awesome repository and how it is executed via GitHub Actions. All you have to do is install it via opam install starred_ml and then opam exec -- starred_ml render > README.md. Voilà! You have your awesome README.

You can customize the template at will. By default the tempalte at default.jingoo is picked up. Here is my awesome template.

Conclusion

I mentioned starred_ml in my last post, and it has been in production since last year (~Apr 2024). Working with OCaml and trying to get this end-to-end journey was a pleasant experience.

I enjoy OCaml quite a lot. It’s functional programming with the right amount of imperative, concise syntax, powerful constructs, and great performance.

It was the first time I decided to go end-to-end, and it was rewarding adventure. Now, I plan to master module semantics better and continue to try dune-release until I get 0-manual work to release future versions of starred_ml.

And the question remains: Why isn’t OCaml more popular?

This is a great question! And I ask the same for Crystal and V. The fact is that not all languages can become popular; there’s simply no such possibility. Furthermore, nobody nailed the formula for popular languages. Some try to put the language behind big names like Go, but see how dart operates on a niche only, built on Google’s shoulders. Others go community-first until the language is picked by big names (see Rust and Zig).

We can’t measure language awesomeness by its popularity. OCaml is very powerful and is slowly modernizing itself and its tooling. We now have things like Riot, dbcaml, Suri Framework, Melange, Miou and should the trend continue, I bet OCaml can become much more common that we are used to.